Our flight took off from Narita an hour ago. Ramen Chemistry is heading back to Oakland after six nonstop days of Japan. Seven ramen restaurants, thirteen different ramens tasted, two sushi dinners, one sushi breakfast, and plenty of culinary exotica consumed, the most foreign—and the most delicious—being shirako soft roe, sacks of fish sperm (shirako means “white children”) in ponzu sauce. Copious amounts of beer and sake were downed in the process. And we had breakfast at Denny’s not once, but twice—twice more than I’ve eaten at an American Denny’s in the past 30 years.

Tokyo Scene. Hama-rikyu Gardens, a former preserve of the Tokugawa Shoguns, backed by the high-rises of Shimbashi.

Along the way, we toured Hiroko’s ramen school and interviewed both the owner and a current student, a former Nissan engineer who is set to open his first ramen restaurant in Chennai, India later this year. We ate at the restaurant of a renowned ramen chef (and one of Hiroko’s ramen senseis), Keiichi Machida, and interviewed him about his life in the ramen world. We walked mile after mile through Tokyo, passing through gardens and shrines, visiting the fabulous Sky Tree, and finding ourselves in the parallel (and fucking amazing) universes of an owl café and a maid café. We finished with a trip to Hiroko’s hometown, where her parents live in a traditional Japanese house—tatami floors, shoji screens, and no furniture—farm their own vegetables, make their own charcoal and salt, and (to our great fortune) catch their own oysters. We took about a thousand pictures.

Ramen chemistry clearly has a lot to talk about. Ramen chemistry also has a day job that starts again in about 30 hours, so let’s see what we can accomplish on this flight before we become delirious. Naturally, we’ll start with ramen.

Tokyo Owl Cafe. Magical experience.

Ramen in Japan

The Japanese eat a lot of ramen. A lot of ramen. There are estimated to be between 30,000 and 40,000 ramen restaurants in Japan. More than once on this very short trip, we encountered a “ramen street” where every shop sells ramen. When we asked a Japanese friend how often she eats ramen, her response spoke volumes about the local baseline. “Not much,” she said, “only about every two weeks.” Compared to this, ramen in America is little more than a culinary parvenu, a novelty item.

That’s rapidly changing, of course, but the reality is that the clusters of ramen restaurants in the Bay Area, NY, and LA—places that have something of an established ramen scene—and the rarefied smattering in the American interior are nowhere near the critical mass in Japan. So while I’ve often thought that San Mateo, CA has a ton of ramen restaurants (there were around five when I lived there a few years ago) compared with my hometown Akron, OH (there are unequivocally zero), San Mateo’s total is only half of that in the underground mall at Tokyo Station. This is all to say that there’s context here: ramen may be hot and trendy in America; in Japan it’s an ingrained part of life.

Tokyo Station "Ramen Street." Restaurant choices (left). Ramen ticket machine (right). This is how you pay at most ramen shops in Japan: pay the machine, get a ticket, hand it to the restaurant staff. The ramen comes to your table. You eat it, then walk out when you're done.

The sheer scale of the ramen industry in Japan and the sheer volume of competition, drive market dynamics in a pretty interesting way. There’s around 10% yearly turnover in the industry. That’s around 3000+ ramen restaurants closing, and 3000+ new ones taking their place. Every year! In the U.S., a ramen shop can often distinguish itself merely by existing. In Japan, more is most definitely required. The outrageous quantity of ramen eaten in Japan gives rise to a commensurate level of ramen sophistication in Japanese ramen consumers.

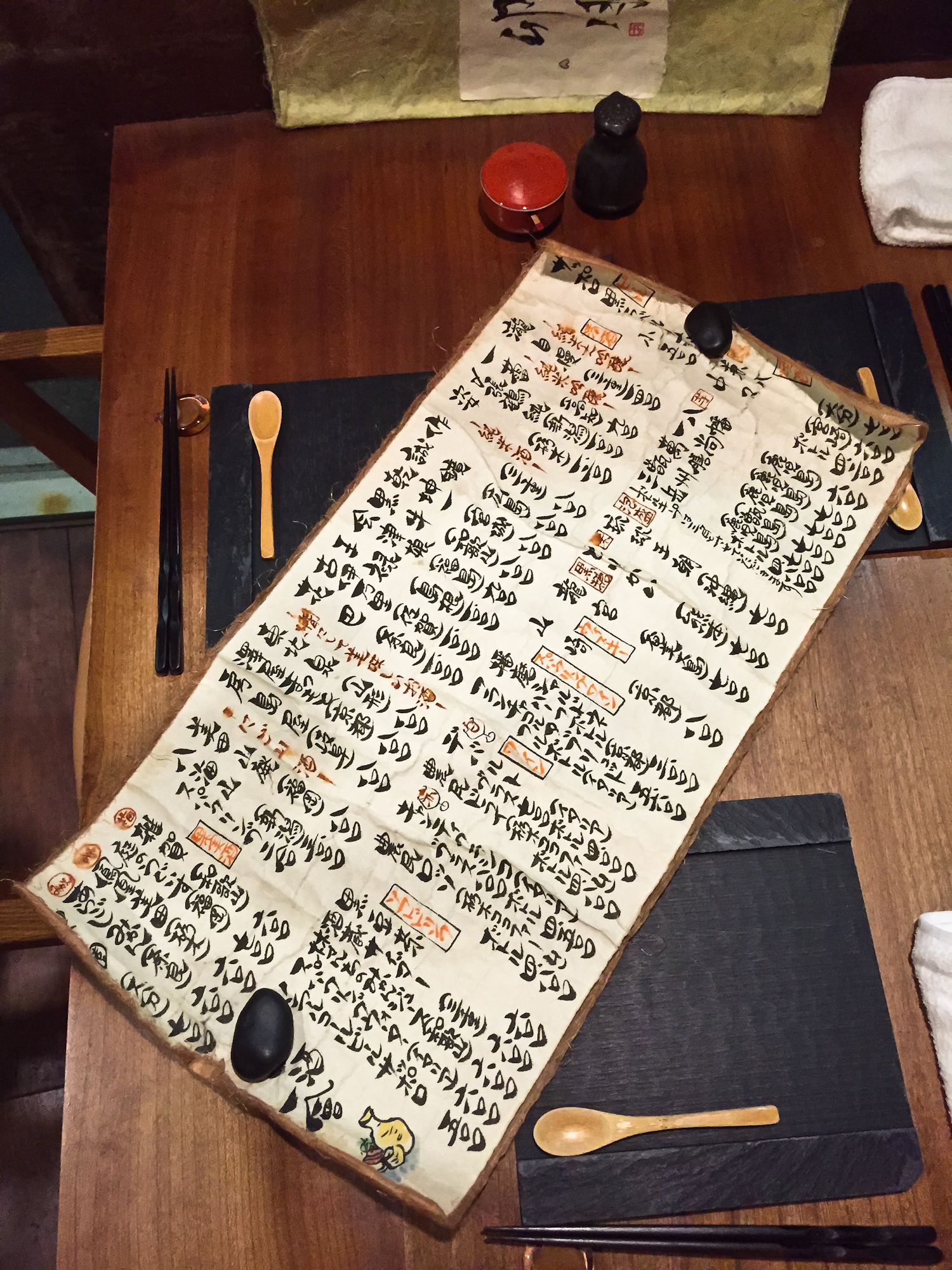

One consequence is that Japanese ramen restaurants often distinguish themselves by focusing on a single type of ramen, or a single dominant flavor profile. We went to one restaurant that specializes in clam ramen, one that specializes in spicy ramens with over-the-top use of high-flavor additives like bonito powder, and one that sells 1500 bowls a day of Yokohama iekei-style ramen (tonkotsu shoyu)—there is literally one item on the menu. On the other hand, there are plenty of chain-style places that serve a wide variety of styles.

The Ramen Scene. Keiichi Machida's Kyouka in Tachikawa.

Another consequence of having such a well-developed and massive industry is that large-scale trends come and go over time. At one time in the 20th Century, ramen trends tended to focus on regional styles, i.e., Sapporo miso or Kyushu tonkotsu. Machida-sensei explained to us that when he started in the industry 15 years ago, ramen trends were driven by the Japanese media’s fascination with—and focus on—celebrity ramen chefs. In subsequent years, thick and rich ramens boomed, but that trend gave way to lighter styles as the costs of ingredients increased (thicker = more bones = more $$). Today, trends favor more minimalist ramens, with tastes that are more unique and individualized.

The point here is that ramen in Japan is as diverse as it is ubiquitous. We went to seven restaurants and had seven very different experiences, and we hardly scratched the surface.

In coming posts, I’ll tell you all about the ramen we ate and the ramen people we met, with lots of pictures. Don’t worry, though, we’ll stop by a maid café soon enough.