Although the most fundamental element of "ramen" is the noodle itself (a special wheat noodle treated with alkaline salts), we tend to think of "ramen" in terms of the soup in which the noodles (usually, but not always) are served. The soup, after all, is the source of so much of the flavor and richness that makes ramen so good. So where does that flavor and richness come from?

Well, it comes from extracting all sorts of compounds like amino acids, polypeptides, and fats from animal bones by boiling them for extended periods. Usually we’re talking about pork and chicken bones. But other flavor sources are also common: dried fish like katsuobushi (bonito flakes) or niboshi (anchovies) are big in Japanese cuisine, as are mushrooms (like shiitake), and kombu (a type of dried seaweed). As you can see in this link and this link (yes, the Umami Information Center does exist), all of these ingredients are big in sources of umami: glutamate and ribonucleotides like guanylate and inosinate. It’s also common to use vegetables like onions, which will endow the soup with added sweetness. In our ramen experiments, we’ve made use of all these things.

The Meats: Pork and Chicken.

Pork is an extremely common ingredient in ramen. In general, we’re talking about pork bones: femur bones, neck bones, back bones. You can make ramen soup with any of these. There doesn't appear to be a strong reason to use one or the other, but some chefs do have a preference. Practically speaking, cost, availability, and process issues are likely to dictate one's choice. For example, femur bones may be more expensive and have a lot of marrow, but you have to break them and cook longer to complete the extraction.

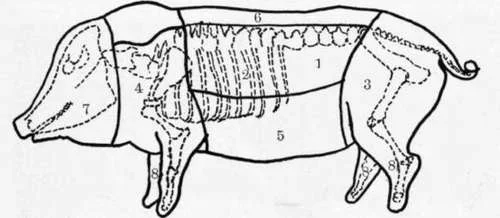

It’s also common to make your chashu topping by boiling pork shoulder (aka pork butt) or pork belly with the bones when making your soup, then removing the meat, marinating it, slicing it, and setting it atop your ramen. And have you ever heard of back fat? This is the layer of fat right under a pig’s back skin. It can be used to add more flavor and thickness to your soup.

Back fat = #6. http://chestofbooks.com/food/science/Domestic-Science-School/Pork.html#.VLXSUouKfWU

Chicken is also very common, and is often used in combination with pork. For some applications, chicken parts are used. I’m talking about chicken backs or frames, chicken necks, and chicken feet. In Japan it’s common to use torigara, which is a cut that includes both the back and the neck. In other applications, a whole chicken can be used.

Soup Categories: Paitan and Chintan

A fundamental point about ramen soups is that they can be loosely divided into two main categories. Paitan (白湯) (meaning “white soup”) is a thick, cloudy soup. Chintan (清湯) (meaning “clear soup”) is clear, exactly as the name implies.

As an example, tonkotsu ramens are almost always paitans. These soups are thick and creamy. They're full of fats and collagens extracted from pork bone marrow and cartilage. The fats provide tons of flavor, while both add body to the soup. If you cool a thick tonkotsu broth, it will rapidly solidify. But you can make chicken paitans, too. These toripaitan ramens have been ascendant in popularity in Japan over the past decade. Although the Japanese tonkotsu boom ended around the time the toripaitan boom began, tonkotsu ramen is still hot in the U.S. Using chicken feet is a key aspect of toripaitan: they are a great source of collagen and soup body.

Ramen School: Hiroko's tonkotsu paitan (left) and a guest chef's chintans (right)

The main difference between paitans and chintans lies in their preparation. Higher temperature and more robust boiling will make a paitan, while chintans are produced by heating at sub-boiling temperatures. High temperature produces an emulsion, which is a mixture of normally immiscible liquids (like oil and water). Lower temperature cooking allows the fats to separate cleanly from the aqueous soup; the fat can be removed and even used later as a flavored oil topping.

Emulsion: Molecular Explanation. Fantastic image from http://blog.ioanacolor.com.

Roughly speaking, pork with its capacity to impart body and richness, is good for making paitans. Chicken, which contains a lot more glutamate (read: more umami) than pork, is good for making chintans. In practice, it's common to combine pork and chicken. And there's a scientific reason for this relating to umami synergy. Look forward to future posts about this fascinating phenomenon.

Next up: Where does a guy buy chicken feet, anyway?