I just flipped our shiba inu calendars to August. Aside 1: How is it August?? Aside 2: Yes, plural. Our love of the shiba is sufficiently well-known that we received two shiba calendars as gifts this year. There's more than one wall here at HQ, after all. But, to my point, it is now August. This is the month Shiba Ramen construction should begin! Our building permits have been issued, and we're seemingly days away from hiring a general contractor. Aside 3: I've said "days away!!" every week for the past month, but getting these contractor bids resolved is an almost unbearably slow process. But this time I really mean it. Maybe.

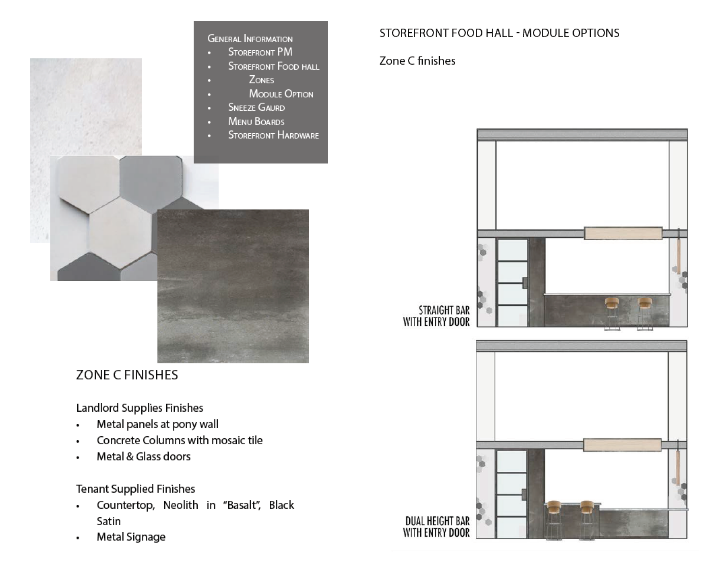

Shiba Ramen. More or less. We've had to cut the bar seating due to obscure regulatory requirements. The storefront elevation diagram below shows the change. This image does not reflect what the tile will actually look like. For a more accurate view, see the image below.

The point, dear readers, is that we have something to build and we're ready to build it. We have a space design that we're really excited about, and that's just a part of the exceedingly complex architectural plans for the whole operation. Seeing how much goes into a sub-400 square foot restaurant space is eye-opening, to say the least.

Over the past few posts, I've explained our approach to space design, from the aesthetic we're trying to create to the many external forces that shaped our decision-making. This time, I'd like to show you where we ended up, and give you a preview of what Shiba Ramen will look like. With any luck, I'll be posting pictures of the real thing in a couple of months.

Storefront Elevation Diagram. Everything to scale. Here you can see that the bar seating has given way to a standing area.

Decisions, Decisions

So here's how we struck a balance between our design goals and the competing constraints on design freedom. We chose to focus on four elements: color, tile, wood, and lighting. The first element--color--was an easy one. Shiba Ramen's signature color is a crimson red, so it is critical that that color is prominently featured in our first location. The storefront sign above our kiosk, a backlit strip of water-jet cut aluminum, seemed like the ideal (and most appropriate) place to deploy the Shiba red. But we wanted the red to play more of an accent role on an overall basis, rather than a dominant one. So we decided to feature it on the edges of our visible shelving and menu board strips. Our pendant lamps are orange-red, not an exact match with the Shiba red. What can you do.

Asanoha Tile.

To accompany the red motif, we decided to incorporate a blue in our tile. Although the hoshi tile comes in "clay" (sort of a brick color), which may well have worked with the red theme, we thought a cool blue would look great as a backdrop for the red. It provides a nice contrast, and because we love blue, we wanted to find a way to incorporate it into the design.

For the tile, the hardest part was finding a place to put it. Because we have to use the landlord's blackened steel panels under-counter, a different location was necessary. We solved this problem by incorporating a customer-facing drop ceiling behind the point of sale. The hoshi tile will be done as a blue-to-white gradient from the left side. We will use a small amount of gray tile to help intermediate the transition. The menu board will hang over the right side of the drop ceiling, directly behind the register.

Wood Elements. Blade sign (left) and mock-up of menu board (right). Prices not to scale.

We are using wood in a couple of ways. First, we'll use a set of engraved plywood strips for the menu board, with the edges painted Shiba red. We'll also use plywood for the blade sign, engraved with the Shiba Ramen logo. But the big wood element is the slatted pine soffit that hangs above the counter and extends down the wall alongside the point of sale. The soffit is comprised of a series of adjacent triangular segments, with the wood in each oriented perpendicular to that in the next. On top of that, the surface is three-dimensional, so that the triangles will undulate along the length of the space. Where the soffit runs down the wall, we will overlay a stenciled asanoha pattern to tie the tile motif into the wood element. Our view is that the angular and geometric nature of the wood soffit will tie in nicely with the similarly angular asanoha tile.

Soffit. This behind-the-counter view shows the three-dimensional nature of the pine soffit.

For the over-counter lighting, we are using a set of four pendant lamps. These so-called "chouchin" lamps are made by an Italian company, Foscarini. But they are inspired by Japanese design. Chouchin are traditional Japanese paper and bamboo lanterns. You've certainly seen them before. The Foscarini lamps are sleek blown glass renderings of this historic lighting element. In other words, it's the exact kind of thing we want to showcase at Shiba Ramen.

Lights! Foscarini's "Chouchin" collection at left. We're using the smaller orange pendant. Japanese chouchin lamps at right.

Note: all of the fantastic images above were produced by our design partner, Misa Grannis. We worked closely with her throughout the process of putting this together. She did the heavy lifting and put together a great design package that we were proud to stand behind. Hiroko and I contributed mostly be musing, opining, and trying not to be annoying.