What makes this restaurant project most satisfying is that we've had the opportunity--yes, the opportunity!--to obtain permission for our activities from at least ten government agencies. And what an opportunity it is. Legions of paperwork, often on actual paper, trips to faceless government offices all over town, and the obligation to lay your neck on the metaphorical chopping block so that some bureaucratic stickler can take a swing.

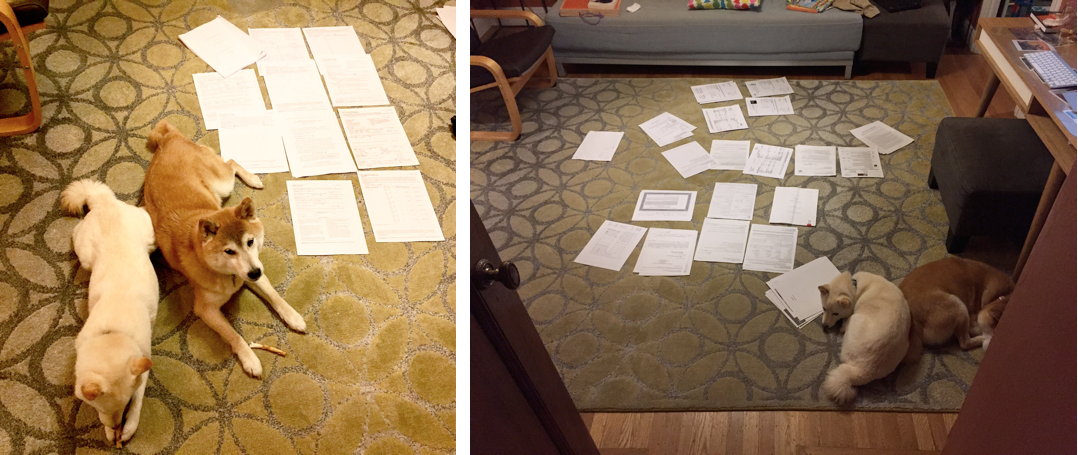

Best of all, you get to pay for the axe! Indeed, the experience calls to mind the execution of the Duke of Monmouth for high treason against the English Crown. Having mounted the scaffold on Tower Hill, Monmouth, "as was usual, gave the headsman some money, and then he begged him to have a care not to treat him so awkwardly as he [had recently done to one unfortunate] Lord Russell." No such luck for poor Monmouth. Eyewitness reports assure us that it took no fewer than five strokes with a blunt axe to have off with his head.

The actual situation is more like death by a thousand cuts: fees upon fees, filings upon filings, building inspectors. Mostly the process is a drag. It's expensive because it's inefficient. Unsurprisingly, it can also be invasive. The worst culprits won't surprise you: the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control, aka "ABC," and the local building and health departments. I've already written at length about the spectacularly overregulated process of getting a license from ABC to sell beer at a California restaurant, which I hope gives aspiring restauranteurs a good sense of what the government has in store for them if they want their business to serve alcohol.

This time, let's do a quick rundown of the basic government interactions you will have when starting your business. Aside from ABC, and to some extent the Health Department, none of this is specific to restaurant businesses. Depending on the nature of your business, who knows which agencies--state, federal, local--you'll have to deal with. So please view this as a general starting point for your startup to-do list, with a slight emphasis on restaurant businesses.

Duke of Monmouth. Head on (L), head (nearly) off (R). I assume this won't be your fate if you forget to file your fictitious business statement, but you probably don't want to test my assumption.

Step 1: Consider Limited Liability and Corporate Structure

So you want to start a business? That's good! And probably also a bit scary, especially if you haven't done it before. The first thing you've got to think about is what kind of business you want to be. And I don't mean what kind of products or services you're planning to sell. I mean what kind of legal structure your business will have. There are a lot of considerations, but the most fundamental is insulating your individual assets from the liabilities of the company. This is the principle of limited liability; i.e., that your risk is limited to what you invest in your company, and does not extend to your house, car, or personal bank accounts.

This is a big topic for another day, but just be aware (1) of the need to legally separate yourself from your business, and (2) that whichever corporate structure you choose--partnership, LLC, S-Corporation, C-Corporation, etc.--will come with its own set of rules governing everything from how you pay taxes, to how you raise money, to what kinds of corporate governance rules you need to follow after you start operating. An LLC is often a good choice for a small business, but every situation is different, and it's probably worth hiring an experienced business lawyer to give you guidance (to be clear, I am not providing legal advice here on Ramen Chemistry). If you want legal advice about your business issues (or know someone who does!) contact me at work at Davis Wright Tremaine LLP.

Corporate Status. We are incorporated in California. Every state's SOS keeps a register like this of every one of its corporations.

Step 2: Endless Government Interaction Awaits. Here's Where You'll Start.

Once you've figured out what kind of entity you're going to be, your first task is to incorporate your company with your state's [1] Secretary of State (here's a link to the CA SOS). This is a simple task involving completion of a document called the Articles of Incorporation (or whatever the appropriate initiating document is for the corporate form you've chosen), paying a filing fee, and--voila--your corporation is born. A person in the eyes of the law! I was so amped up to start Shiba Ramen two years ago that I got up one morning to pay a personal visit to the SOS office in Sacramento to file our Articles. Completely unnecessary, and naturally anticlimactic, but I'm glad I went anyway.

If you're planning to sell taxable goods (ramen, burritos, consumer electronics, whatever), you'll need to get a Seller's Permit. In California, you get this from the [2] state Board of Equalization. This permit allows you to purchase goods for your business without paying sales tax, so long as those goods are intended for resale. The idea is that a sales or use tax is paid only by the end purchaser. For example, we don't pay sales tax on drinks when we buy them from a wholesaler, but we charge tax when we sell them to customers. As a seller of goods, your responsibility is to collect that tax from your customers and remit it to the state.

You'll probably need to file a Fictitious Name Statement in any counties where you do business. Here in Alameda County, this is done at the [3] Clerk-Recorder's Office in Downtown Oakland. So what's a fictitious business name? This is the name under which you actually do business (i.e., your "DBA name"). If your DBA name is different from the official name of your corporation, you need to register it with the county. So, for example, Shiba Ramen Corporation is our official name, but Shiba Ramen is our DBA name. We filed a Fictitious Business Statement on Shiba Ramen. After you file the registration, though, you're not done. You then need to publish a notice in a legal newspaper for several weeks in a row before you are permitted to use your DBA name.

Assuming you issue shares in your company (as we do for our S-Corp), you'll file a Notice of Issuance of Shares with the [4] California Department of Business Oversight. You'll need to get a business license from the [5] city where you do business. In Emeryville where we do business, this is given in exchange for a yearly tax payment of 0.1% of annual gross revenue.

Once you start operating, you'll be in regular contact with the [6] Franchise Tax Board, to whom you'll remit sales taxes, and the [7] Employment Development Department (aka "EDD"), to whom you'll report data on your employees and remit employment taxes. Food businesses will deal with [8] the county Health Department and possibly [9] ABC. Any business that builds anything must go through [10] the city Building Department.

You didn't think there'd be any one-stop shopping in the world of government permits and taxes, did you? The good news is that the basic startup cycle is long enough that you have plenty of time to figure out the steps and get them done. Most of these things you can do on your own as long as you do some research in advance. There are a lot of great corporate startup guides and web resources to guide you through the steps. I relied pretty heavily on a couple of CA-specific guides from Nolo, which were extremely helpful for a project like Shiba Ramen. These are written in everyday language, are comprehensive, cover a huge scope of topics in many states, and are instantly downloadable. You can always call an attorney if something feels too far out of your comfort zone.