Remember just over a year ago, Halloween 2016, when you were thinking to yourself, "man, this year fucking sucked, it can't end soon enough." In due course, you got your wish. 2016 ended, just as experts had predicted it would, but not exactly in the way anyone expected. As the December days fell away, you were suddenly all desperation, clinging to what you were coming to realize wasn't such a bad year after all, relatively speaking. You wistfully swooned over Barack Obama's farewell tour, living brief weeks in a halcyon present, the rising tide of nostalgia concealing undercurrents of dread for the year that was to come.

In between feel-good retrospectives and holiday parties, you daydreamed that the Universe still might bail us all out. In your imagination, a massive sinkhole opened up and swallowed Trump Tower, whisking its human cargo straight to Tartarus for a thousand lifetimes of torment. But fantasy didn't get you very far before you remembered Donald already owns a golf course down there--Trump Underworld National CC--and is reportedly trying to do a licensing deal for a Trump Tower somewhere in the bowels of hell. If anything in the State of New York gets devoured by a sinkhole, you concluded with a sigh, it's going to be a house in Chappaqua, not a Midtown highrise. After all, hadn't Trump, or maybe some sinister, spectral creature in the form of Rudy Giuliani, promised to lock Hillary Clinton up for eternity?

Sinkhole. Actually, one opened up in front of Mar-a-Lago in May 2017. Photo credit: Palm Beach Daily News.

When the New Year came, the world still turned on its axis, the same as it had always done. Obama was still President; you got a twenty-day reprieve from whatever horrors 2017 had in store. At that point, though, you couldn't even contemplate life beyond Inauguration Day, the future as unknowable as you'd ever known it to be. But even if you imagined the gross corruption and the nuclear brinkmanship a la Twitter, to say nothing of the hurricanes and earthquakes and shootings--all predictable enough--you didn't imagine their scale or their scope. At Halloween 2016, you actually thought 2017 would deliver you from the Internet-news-cycle zombie-ism to which you'd fallen prey. But if you'd closed your eyes and listened closely, you would have heard a faint voice: "What's up bitches," whispered 2017, "I'm waiting out here, on the other side of your January horizon, and I'm going to fucking eat you all."

So here we find ourselves, a year later, maybe more zombie than human by now. The news cycle never ends, the Internet is a cancer on our productivity, our capacity for concentration is shot. I don't need to enumerate the specifics for you; you lived through them just like I did. The world is on fire, and we are choking on the smoke. I'm not just saying this metaphorically. The skies of October here in the Bay Area were all orange haze and falling ash, as wildfires burned out of control in Wine Country. Every morning for a week we awoke, our houses smelling as if we'd slept next to campfires, rather than in the comfort of our beds. The children couldn't play outside at school. It was disconcerting and disorienting for us, and devastating for our neighbors to the north.

Sonoma Wildfire & 2017 Natural Disasters

That's not to say that 2017 has been all bad. Just think back to that Monday morning a few weeks ago, when Robert Mueller offered up the comically ham-fisted colluder George Papadopoulos, a small sacrifice to restore order in the Universe. How, you wondered, did this tyro of a douchebag get a seat at table in the first place, his only qualification to be a presidential foreign policy adviser being participation in Model UN, the details of which he apparently lied about. He looks like the kind of low-level thug that gets killed in the first scene of an action movie. You know what I mean?

In that sense, from Papadopoulos's perspective, it's a win that he arguably made it to Act II before getting killed off. Now he's famous! As a matter of fact, his role is likely to blossom, as we learn about all the conversations he had with other douchebags when he was wearing a wire between his July arrest and October plea agreement. But what of Jared, Junior, and Jeffrey Beauregard Sessions III? The Universe surely requires their sacrifices, too, before any semblance of order can return. Seeing those three assclowns in orange jumpsuits, as satisfying as it would be, still wouldn't cure the disease that made them household names in the first place. In other words, more sacrifices are coming, rest assured, but we have bigger problems on our hands. I realize I'm not telling you anything you don't already know. Public life in 2017, we can safely conclude, was a shitshow the likes of which we American Gen-Xers and Millenials haven't seen in our lifetimes. 2016 was an epic teaser trailer, for sure, but no matter how shitty that year seemed, that's all it really was.

Papadopoulos Collage. "Following his arrest, defendant . . . met with the Government on numerous occasions to provide information and answer questions." Upper left is the infamous meeting, unremembered by Jeff Sessions until later remembered by Jeff Sessions, at which Papadopoulos suggested connecting with the Russian government.

What about private life in 2017? Ramen Chemistry is nominally about our restaurant business, frequent digressions notwithstanding, and there is a lot to say on that front. Before I get started though, as an aside, I take this opportunity to report a new finding made last night: just because fish at the farmers market is labeled "sashimi grade," does not mean you should eat it as sashimi.

Anyhow, it was indeed a big year for our restaurant business. You might even say a banner year, although it hasn't felt that way, and not in terms of sales. We opened two new stores this year, Shiba Ramen Oakland in February and The Periodic Table in September. As I've mentioned on these pages before, both were expensive undertakings and we had to stretch as hard as we could to get them off the ground. Both projects opened 1-2 months after their target dates. In the case of Oakland, that caused us to miss a large chunk of peak ramen season.

Meanwhile, clouds have hung over our Emeryville business since early spring, with a massive exterior construction project displacing parking, disrupting traffic, and essentially operating as a moat around the food hall. Business dropped around 10% relative to 2016, which in the restaurant business is where all the profit is. The sales differential in the affected period is over $60,000 to date, and still growing. The new road still isn't open, although we're told it will be in a few more weeks, but only after we endure the closure of southbound traffic during the final week of paving. The big anchor grocery that was supposed to be open already just pushed back its opening until March.

More Stars of 2017.

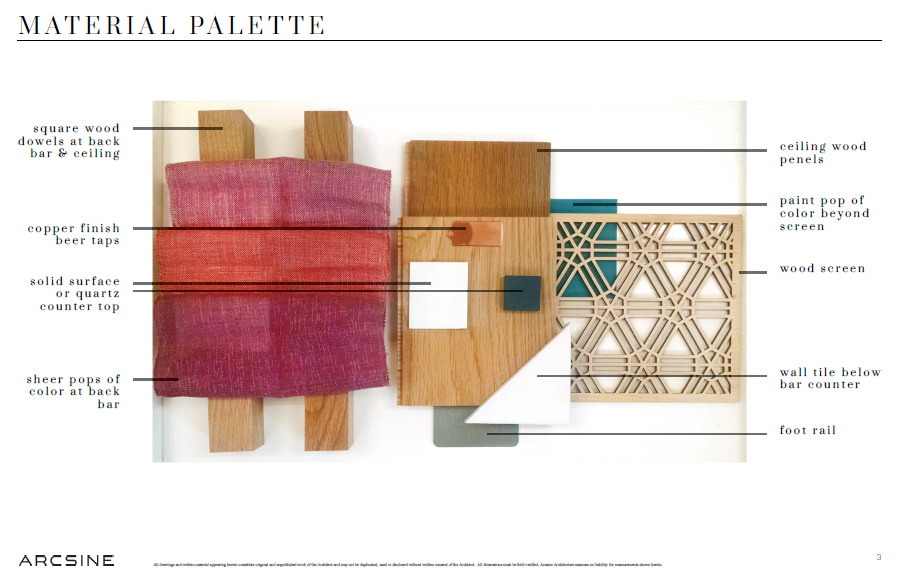

It was in this environment that we opened The Periodic Table, just as September--the weakest month of the year for Shiba Ramen--was beginning. Public Market was a lunch hall historically, and it doesn't have a reputation as a place to go drinking. We expect that to change over time, when more bars are in the facility, when the grocery and the 500 new condos are open, when it can credibly draw nighttime traffic. But we didn't expect things to start as slowly as they have. Alcohol sales are not exactly strong, and a significant portion is just cannibalism of Shiba Ramen's beer and sake sales.

People don't drink much at lunch, and the Market itself isn't currently capable of drawing much foot traffic after 8 p.m., so we're getting squeezed. Whereas being in a food hall helped Shiba Ramen to be instantly successful, it's having the opposite effect this time around--it's not capable of delivering the type of traffic we need to be profitable doing something other than a fast-casual food concept, particularly now with the construction disruptions. Certainly the longer-term prognosis for the Market is much more positive, but it's clear we're going to have to work a lot harder than the food kiosks to drive our own traffic.

We're doing our best to get the word out--$3K/month PR spend plus lots of social media--and a ton of great press has resulted. Other programs are in the works, starting with a sake/food pairing event (with lecture by yours truly) next month. Disappointment about initial sales notwithstanding, I feel very good about the product we're selling. The alcohol selection is exemplary, and getting better as we add products and build out a solid cocktail menu. The burger is very good, but we need to find a way to sell more. We also need to find a way to sell a couple more lunch items to increase food sales until alcohol sales are capable of standing on their own.

Construction. Story of the year.

My optimistic long-term outlook for the business is all well and good (and helps keep the motivation up) but things are still pretty painful today. Hiroko hasn't gotten paid in six months, and she's basically a prisoner of The Periodic Table on weekdays because there is no money to hire a bartender. The financial strain is taking a toll, although with the weather finally changing, I think we've passed through the worst of 2017 from the perspective of Shiba Ramen Corporation. The structure is now in place, so we have to figure out how to make money--and wait for the development to fill in around us and drive more natural traffic. That goes for our Oakland store, too, which is also in the midst of a ton of large-scale but still unrealized development.

Meanwhile, I'm still practicing law everyday, and doing the bulk of the childcare around the house. Preschool is great, but it's damn expensive and they are on vacation all the fucking time. Three weeks in August, a week again starting tomorrow, and every pseudo-government holiday in between. As is true of so many people of our generation, we're living our life out here on an island, far from where we came from and without a support network. When I was a kid there seemed to be other kids and relatives and stay-at-home moms everywhere. Today everyone works all the time; families and friends are not down the street. We manage everything ourselves, except what we can afford to outsource.

For months my mood has been dour, continuing this juggling act day after day with no respite, and no end in sight. External circumstances--the National Dumpster Fire and the ramen sales climate--add pressure to an already challenging situation. I feel exhausted when I wake up, in the morning my thoughts are viscous and unfocused, I require celebratory drinks in the evening as a reward for getting through the day. Nightly, after the bedtime routine, my face contorts at the thought of returning to my desk and facing the computer again. It's hard to get anything done. Something has to give at some point, doesn't it?

Successful Projects. Now they need to make money!

How should I feel about 2018? Well, how do you feel about it? Shit could definitely get worse, especially out there in the world. I'm not expecting deus ex machina in the form of an impeachment, but I could, however, imagine the chief executive choking on a chicken finger or a mozzarella stick; I just don't think it will go down that way, or that Presidential demise by rogue jalapeno popper is going to solve the bigger problems we're facing anyway. But for the time being I will relish the indictments as they unfold. General Flynn and son, are you gentlemen up next? As a new year's resolution I will try to look at the Internet less and get out of the house more.

On the business front, I'm optimistic. We're not building any more restaurants until the ones we have are making money, so no more capital expenses. Sales likely improve across the board as development progresses, and as we build our reputation. The coffers become replenished, and mental health improves accordingly. Whether it goes down this way or not remains to be seen, but for now I say, l'll say what I said at Halloween 2016: "man, this year fucking sucked, it can't end soon enough." I'll add, "let's give it up for 2018."

These Three. 2017 wasn't all bad.