Now we’ve worked our way through arguably the two most important components of ramen, soup and tare. The combination of soup and tare goes a long way toward defining the flavor and quality of a bowl of ramen. But the overall experience of a given bowl can—and will—vary wildly depending on everything else that’s in it. Everything else means noodles, oils, and toppings.

Noodle Basics

Ramen noodles are alkaline wheat noodles, made from flour, water, salt, and carbonate salts like potassium carbonate (K2CO3). The word “alkaline” refers to the basic pH of added carbonates. As this recent column explains, taking the pH to about 9.0 (remember neutral pH is 7.0), natural yellow pigments are released, “giving the noodles a characteristic golden hue. Alkalinity also encourages greater absorption of water in the flour, more starch degradation, and an increase in strength and extensibility. . . . The starch gel within the protein matrix is also strengthened, resulting in a firm, chewy bite.” In other words, it’s the alkalinity that makes a ramen noodle a ramen noodle.

Good old potassium carbonate. You and I spent a lot of time together during the last Bush Administration.

The composition of ramen noodles is variable. Flour can range from 50-70%, water from 25-50%, and carbonates (kansui in Japanese) from 1-3%. Unsurprisingly, noodles with higher water content are softer. Noodles with less water are more powdery and have a rougher texture. They also have a more floury taste. And they are less springy and absorb water (and become soggy) more readily.

The type of flour used impacts the properties of the noodle. This is because different types of flour have different levels of protein content. The more protein in a flour, the more gluten will be present in the noodle, and the more chewy and elastic the noodle texture will be. Gluten (in addition to being the leading dietary bogeyman of the past decade) is a composite of two naturally-occurring wheat proteins, gliadin and glutenin, that forms during the kneading process.

Creating Noodle Elasticity. As the Royal Society of Chemistry explains, "as mechanical work stretches the dough, more hydrogen bonds (black) can form between chains of gluten subunits (orange)." Great article on the chemistry here: http://www.rsc.org/chemistryworld/Issues/2009/October/Ontherise.asp.

The shape of the noodle is also important. The thickness of the noodle influences the sensory experience, the rate of absorption of broth, and the amount of soup that is eaten in a given bite along with the noodles. Noodles are numbered according to their thicknesses, which are set based on the number and size of the teeth in the noodle machine.

By adjusting these variables--the ratio of water, flour and carbonates, and the thickness and shape of the noodle--you can technically achieve infinite variety in ramen noodles.

Noodle Varieties. Sun Noodle's product line. http://sunnoodle.com/our-noodles/

Noodles in Practice

Shiba Ramen is going to buy its noodles, just like most other ramen shops do. It's easy to buy a wide range of quality and fresh noodles from various wholesalers. Doing so makes sense from an operational perspective, because you don't have to allocate scarce resources to the non-trivial and constant demands of making noodles. This is especially case early in the life of the business.

Of course, some ramen shops do make their own noodles. They use noodle machines: big pieces of equipment that cost between $10K and $30K in Japan. These things can make 100-300 servings/hour.

Cooking the noodles the right length of time is critical. Noodles that are overcooked or waterlogged are hard to eat, and can ruin an otherwise good ramen. It’s just as important to serve (and eat) them quickly after cooking them. The longer the noodles sit in the bowl, the more soup they’ll absorb and the soggier they’ll get. Quality control is achieved by using a restaurant-grade noodle or pasta cooking machine with a timer. And, of course, by paying attention to what you're doing!

Noodle Machine Catalogue. http://www.yamatomfg.com/item/richmen/

Oils

Oils are often used to enhance the sensory experience of a bowl of ramen. It makes sense—fats are full of flavor, after all. Because the oil sits on top , it's the first thing to hit your spoon when you scoop up some broth, and the noodles pass through it as you eat them, too, picking up flavor along the way.

You can pretty much make an oil out of any ingredient, so oils are a great way to add some flavor punch to a bowl of ramen. You may have seen blackened garlic oils or spicy chili oils (like la-yu) at ramen restaurants. You can even use the clear, golden chicken oil that rises to the top when making a chintan soup. Pork back fat can also be used. And have you ever had shio butter ramen? It's served with a chunk of butter dropped into the hot soup. Yes, it's good.

Toppings

If you've eaten very much ramen, you already know there are no real rules for topping ramen. Slices of pork chashu, soft-boiled egg, menma, negi (green onion), and nori paper are pretty conventional, and it might be expected that one or more of these ingredients will come with a bowl of ramen. Some of Shiba Ramen's menu items will feature these standards.

There's a ton of flexibility, though, and chefs are hardly limited to this traditional set of toppings. As Ramen Chemistry develops, I'll make sure to show a lot of ramen, both ours and others, so readers can get a sense of the range that's out there.

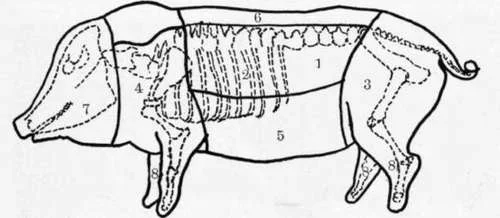

Chashu. This article has a great recipe and discussion: http://www.seriouseats.com/2012/03/the-food-lab-ramen-edition-how-to-make-chashu-pork-belly.html.